(Note: I am an attorney, but I may or may not be licensed in the jurisdiction of any particular reader. Nothing in this post constitutes legal advice. Consult an attorney licensed in your jurisdiction and familiar with the relevant law before making legal decisions.)

Gather ’round, everybody: it’s time for another episode of Stupid Legal Tricks!

Today, we’ll be learning about design patents. They’re like if a copyright and a utility patent had a Science Baby, then used trademark DNA to augment it. The whole thing is then engineered to reflect the worst parts of its parents and unleash horror on an unsuspecting world! (Editor’s Note: So, like Deus Ex: Invisible War?)

Okay maybe not quite that bad, but bad enough, and for indie game developers, potentially nearly that bad. The fact that even if you’ve heard of copyrights (you probably have) and patents (ditto) you may never have heard of design patents should tell you what one problem is. Even for esoteric intellectual property, design patents have, historically, been pretty obscure. So, what are they? I’m glad you asked.

Design patents are a type of patent which protects the ornamental design of articles of manufacture. That is, the underlying thing has to be an article of manufacture, but what you’re getting protection on is the appearance of it, not the thing itself. Clear?

No? Can’t blame you.

In a modern law context design patents are stupid. Or, at least, largely redundant. However, they’ve been part of the patent law for over a hundred years, and the idea actually has a sort of reasonable basis. Namely, to help bridge the gap between copyright and patent in days gone by. Back then, copyrights were a lot weaker, as was trademark law, and often neither could be extended to the form of useful articles at all. So the idea was that if somebody went to the trouble of making a nice ornamental design for a useful article, we’d give them some commercial protection for it.

What Is a Design Patent?

It’s probably closest, in pure concept, to a copyright. But the term is much shorter than that of a copyright (currently, fifteen years from date of issue,) and it’s far harder to infringe a design patent: unlike a copyright, there is no such thing as a derivative work of a design patent. Either the alleged infringing article is confusingly similar to the patented design, or it isn’t. If it isn’t, no infringement can occur.

That confusion must take place in the mind of a hypothetical reasonable consumer, which is where the trademark DNA gets switched on, because of the Big Three (copyright, utility patent, trademark) the only one where we care about confusion at all, let alone marketplace confusion, is with trademarks.

To round it all out, it’s like a utility patent in that it’s issued by the Patent Office, only a patent lawyer can apply for one (any lawyer can apply for a trademark or a copyright) and it’s much more expensive – hundreds of dollars in application fees, plus costs more like prosecuting a utility patent. And there’s no parallel development defense, such as one might see with a copyright. Nor is there a fair use or nominative defense, such as one might see with either copyright or trademark. Design patent infringement, like regular patent infringement, is pretty much a “strict liability” sort of thing. That means your intent is irrelevant for the most part. We might care when it comes to calculating extra sanctions like attorney’s fees or statutory damages, but not in determining whether you’re liable in the first place.

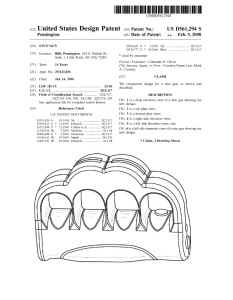

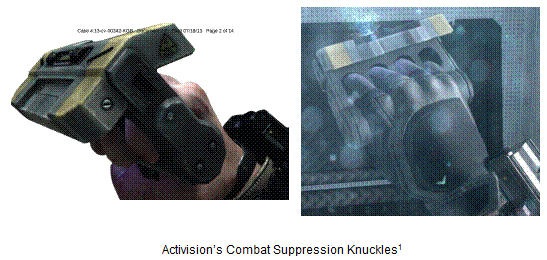

Here’s what a design patent looks like:

Design Patents and Video Games

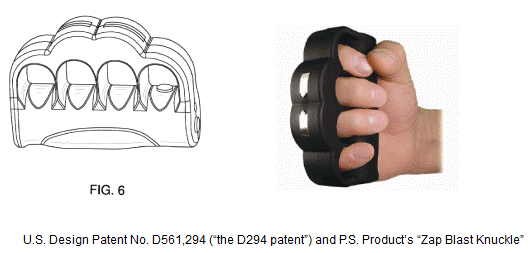

As you may have guessed – You’re very clever, have I mentioned that? – I didn’t pick this example at random. This was one of the two patents, both design patents, at issue in P.S. PRODUCTS, INC. v. ACTIVISION BLIZZARD, INC. (E.D. Arkansas, February 21, 2014.) The design patent is for a physical stun gun which you can wear like brass knuckles. (Don’t, though, because it’s probably illegal.)

Activision made an allegedly similar virtual stun gun and put it in their game Call of Duty: Black Ops II. The court dismissed the suit and told P.S. Products, the owner of the design patents, the following:

- The stun gun in the game didn’t look enough like the one in the design patent claims:

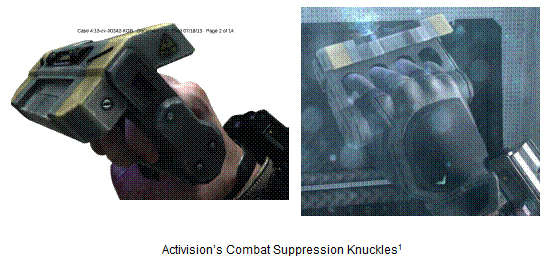

The virtual stun gun. so there was probably no infringement, which was irrelevant because…

- This is a design patent for a real thing a person can wear and Activision is selling a video game, you morons.

No reasonable consumer would buy the game thinking they would get the patented product, so therefore it is impossible for an infringement to occur. Big win for the game community. (If this had gone the other way, the consequences could have been disastrous for game developers and other people who create artificial realities, and I am completely serious.) This is just a District Court decision and who knows what a Federal Appeals court or the Supreme Court (*shudder*) might do, but it appears to be solid legally at this time. Bottom line: Design patents for real things can’t be infringed by virtual things.

But…

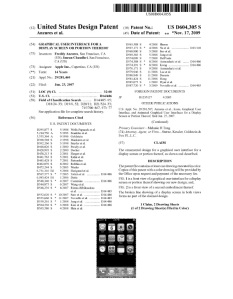

You can get a design patent for a virtual thing. Kinda. If you are into gizmos and gadgets at all, you may have heard that two obscure hardware companies called Apple and Samsung have spent the GDP of a medium-sized state suing each other over patents the past few years. What you may not know is that the patents in question, at least the ones that produced the significant-fraction-of-a-billion-dollars in judgments, were design patents. Here’s one:

That’s right, tens of millions in legal fees, hundreds of millions in damages, and at least one trip to the Supreme Court (so far) and this is about a graphical user interface. Every game designer reading this, if they’re paying attention, just felt a cold, cold wind on the back of their necks.

Because this now opens the door to patenting, not copyrighting, portions of a game’s interface. Or of any interface, and then claiming that a particular product – like, say, a video game – has a confusingly similar interface. Or significant element. Or who knows what? Nobody, that’s who.

Now What?

What can you, the well-meaning indie game developer, do about it?

In one sense, not a lot. For most indies, it’s prohibitively expensive to do a “freedom to operate” search for design patents. And without that, the risk is ultimately unknowable.

But in a practical sense, there are two things you can do that will help lower your odds of being accused of infringing. And this works sort of like being hit by lightning*. If you get hit by lightning, you are going to be in a world of hurt unless you do something completely ridiculous like walking around in a mobile Faraday cage; but to not get hit in the first place, you just need to not go where lightning is. You still might win (or lose?) the Lightning Lottery, like this poor bastard: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Sullivan. But your odds will go way down.

Here are the two things:

- Don’t put confusingly similar copies of interfaces or significant game elements made by other people in your game. That’s the big one. Make. Your. Own. Stuff. The nice thing about this one is that it’s free. The bad thing about this one is you have nobody’s opinion but your own to go by.

- If you think your game might have a confusingly similar interface or significant game elements to another game, whether you meant to or not, ask a patent lawyer familiar with video games and design patents to look at your game and give you a general opinion. The bad thing about this one is it’s not free. The nice thing about this one is that it’s much more reliable than the first one. An “opinion of counsel” to lean on can sometimes help in arguing about certain kinds of damages and it’s always better than a sharp stick in the eye.

Patent lawyers can even provide “infringement opinions” on whether your game might infringe on any particular patent, which is much, much cheaper than a general “freedom to operate” opinion. There are lots of limitations in such opinions, but they are tremendously valuable, and much cheaper than defending even the simplest, lamest patent infringement case. Likewise, they can try to find out if there are any design patents on the game interface you *ahem* innocently and completely by accident made a near-perfect replica of. That’s harder, since there’s always a possibility of missing one or one issuing after you do your search (design patents, like utility patents, are secret until issued.) but it’s still doable.

Now that we’ve had our whirlwind tour of the world of design patents, I’ll let you in on why I bring this up in the first place.

The number of design patents being filed is increasing dramatically.

That Activision case is from 2014. The Apple/Samsung case was decided by the Supreme Court in December of 2016 (and is, technically, still ongoing as of this writing since the Supremes remanded it back down to the lower courts.) This area of the law, after decades of relative obscurity, has exploded onto the tech scene. And if there’s anything big companies like, it’s ways to keep smaller companies and independent developers from horning in on their territory. They’ve all seen the future, and it is design patents.

Speaking of, should you, the intrepid independent developer, consider filing design patents on your game elements? The answer, as always in law, is “it depends.” If you have the money, yes, you absolutely should think about it. Especially if you have come up with a new, nifty sort of interface for your game. If you don’t have the money – or if that money would be better spent making your game better – then you shouldn’t worry about it.

Also, if you don’t have the kind of budget it takes to enforce a design patent once you get one (Spoiler: Tens of thousands of dollars.) then realistically, there’s not much point in getting one unless you hope to sell your game to somebody with deeper pockets. Patents are a heck of a marketing feature, though, so if you are thinking along those lines, it might be worth your while to see if the budget can swing a patent application.

As always if you have questions, leave a comment here, email me or say hi on Twitter. Thanks for reading!

*Hat tip: Ryan Morrison, the Video Game Attorney, from whom I stole this metaphor before improving it dramatically.

Very interesting. I’m an attorney near Silicon Valley with enough knowledge of IP to recognize this appears accurate, as well as accessible & useful to game designers. Well done.

LikeLike